Mammoths roamed the Eastern United States, just 9,000 year ago.Unbelievably, Steve and I were beat out by actor Ted Danson. Danson

Mammoths roamed the Eastern United States, just 9,000 year ago.Unbelievably, Steve and I were beat out by actor Ted Danson. Danson beat us with simple logic, arguing in his "long bet" with Mike Elliot (editor-at-large of

Time magazine) that the Red Sox would win the World Series before the US men's soccer team would win the World Cup. As Mr. Danson explained:

"The Red Sox have had such bad luck in the 20th century, I have to believe that in the new millennium it can only get better. Besides, statistically, scoring goals is harder than hitting a home run, and in the World Cup, you have the whole WORLD against you, but in baseball, the Red Sox only really have to beat the Yankees."

Danson was right. As a consequence, Steven and I will forever be minor footnotes in the history of

Long Bets.

Damn that Ted Danson!But I get ahead of myself. Let us start at the beginning.

But which beginning?That's always a puzzler for me. When in doubt, I generally start chronologically, so I guess I will do that this time too.

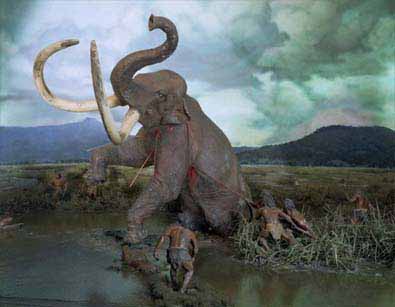

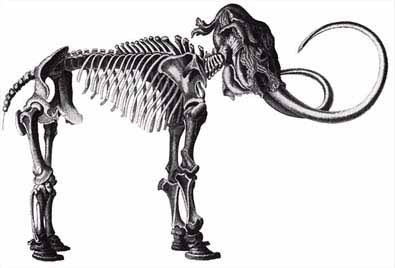

We will start 10,000 years ago. Ten thousand years ago we had mammoths roaming around my back yard. As far as anyone knows, humans had no written language. Humans had just arrived in North America. No one knew who Bill Gates was.

It was a long time ago. About 10,000 years ago humans came and spread across this hemisphere. The result was

a massive die-off of many large animal species, including the mammoth.

It was more than simply the arrival of the Clovis Point; it was also that humans, with limited ability to store knowledge or record history, had no foresight and no communication. Humans had no past and no future. All we had was a short "now."

Let's jump ahead a few years -- to 1996. That's the year

Brian Eno,

Stewart Brand and

Danny Hillis began an extended conversation about the future. Back in the 1970s and 1980s, when folks were talking about energy, water, population, and economics, everyone was keying their predictions to the year 2000.

But it was 1996 now, and the year 2000 was right around the corner. What was the "Next Future" going to be?

The obvious thing to do was to simply set a new "future point" 20 or 50 years ahead. The obvious thing to do, however, is not necessarily the

genius thing to do. The genius looks at the question upside down and sideways, challenges the base line, and thinks in four and five dimensions (time and space), not just three. And so

Brian Eno,

Stewart Brand and

Danny Hillis (

true geniuses all), leaped the fence of convention and began to think about 10,000 years.

- 10,000 years is about the age of the oldest living thing on earth -- the bristle cone pine.

- 10,000 years is about the time that man first began to turn the wolf into the dog and when the first clay pots were made.

- 10,000 years ago is about the time that man first began to irreperably hammer-damage the planet.

The human ability to wreck things has expanded exponentially faster than our ability to consider the future.

Clovis points have been replaced by "Daisy Cutter" bombs, dams large enough to flood entire civilizations, and mountaintop removal.

And yet most people still have not planned for their own retirement, much less considered the ramifications of genetic engineering, or the building of entire cities on rapidly dwindling reservoirs of fossil water.

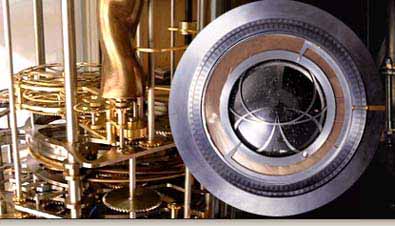

And so, in order to try to shift the time paradigm, Steward Brand, Danny Hillis and Brian Eno decided to build a clock -- a physical, visible thing that would run for 10,000 years. The clock would chime once every 1,000 years, and its very presence would require a different kind of thinking about the future.

What would power the clock? Solar power needs too much maintenance and so too does nuclear power. Could geothermal energy do the job? What power source would never run down and would never submit a bill? And thus was born the beginning of the struggle to answer the first great design question: what would power the clock?

Who would maintain the clock? Clearly not one person, so there would have to be an organizational structure -- and thus was born the Long Now Foundation.

Where would the clock be located? It had to be some spot free from destruction for 10,000 years. And so the Long Now Foundation purchased part of a mountain in Nevada where the clock will be situated deep inside a limetone cliff.

Who would explain the clock? Ten thousand years from now people will not be using any language we know today. And so was born the Rosetta Disk to serve as a translation tool for the future.

The 10,000 year clock being built by the Long Now Foundation.

Changing a paradigm is not easy. In fact, it is so hard, and so rarely done, that the very idea of it seems more than a little Quixotic.

And yet all important change comes from paradigm shifts, and a paradigm shift about time is, I think, exactly what humans need. Or, as Stewart Brand has put it, "we need to think slower and deeper, not faster."

But to tell the truth, a 10,000 year clock is a little abstract for most people. Never mind that it is physical and visible and magically corrects itself for the long-term global wobble that will result in a deviation in solar time.

People are simply unable to grasp 10,000 years. They have more immediate concerns. Like lunch.

In any case, the future is not built in a 10,000 year lump any more than a cathedral is forged from a single block of stone.

The future will be built like a cathedral, made up of thousands of blocks of action and consequence, each carefully cut and interlocked into place.

And so was born "Long Bets," to promote more robust short-term thinking. Better building blocks to make a better cathedral.

The Long Bets idea was forged when Paul Ehrlich said he would give even odds as to whether Great Britain existed in 2000. Ehrlich was prone to making such provocative apocalyptic statements. His most famous book, "The Population Bomb," predicted massive die-offs in the developing world due to a shortage of food and a "longage" of people.

In fact, such predictions started with Malthus who postulated that population grew exponentially and food arithmatically, and for that reason doom was inevitable and that aiding the poor was foolish and would only abet more misery.

Malthus's tract on population was written to justify land clearances for the Enclosure Movement. Without writing a long essay on Malthus, it is enough to say that he was quite wrong. Since Malthus' time, global food production has outpaced human population growth, life expectancy at birth has increased, and literacy has spread.

Those facts, of course, have not stopped a small parade of apocalyptic predictors from following Malthus, from William Vogt to Paul Ehrlich, Garrett Hardin and William Paddock.

On the other side of the coin have been a few people like Julian Simon -- a University of Maryland economics professor who claimed human ingenuity could solve ALL problems. I will not delve into Simon's intellectual mistakes, but they are as legion as any of those on the opposite side of the coin. My aim here is not to get trapped in the quagmore of Ehrlich and Simon. What we are talking about here is Long Bets -- let's get back to the Long Bet that was made.

Simon challenged Ehrlich to bet on the future price of any 10 commodities. The bet would last 10 years, and the winner would pocket the price differential in the commodities.

Ehrlich quickly accepted the challenge, picked a portfolio of 10 metals, and crowed that he would make out like a bandit.

Ten years later, however, when the value of the portfolio was added up, it turned out that every single metal had declined in value.

Simon pocketed Ehrlich's check with a wink and a nod.

Much has been written about this bet in the past, (google Simon Ehrlich bet). I will not delve into it too deeply other than to say that both men were overly simplistic in their analysis of both resource use, pricing and population.

That said, the idea of a financial bet between two parties intrigued Stewart Brand and his small band of talented brethren.

In their quest to promote "slower and better" thinking, a "Long Bet" seemed like an excellent mechanism to encourage both increased participation and better prognostication.

Money has a way of focusing the mind.

And so was born LongBets.org.

I came across this web site five years ago when I was looking into what Stewart Brand was now up to. Brand had been the creater of The Whole Earth Catalogue -- a series of simple catalogue-like publications, assembled by a merry band of hippies, that were so sweeping in their interests that Steve Jobs (of Apple Computer fame) has credited Brand with creating the paper-and-print conceptual forerunner of the World Wide Web.

All I know is that The Last Whole Earth Catalogue is still worth reading -- again and again -- even today.

When I checked out the Long Bets web site I found some real brainiacs making serious bets -- people like physicist Freeman Dyson, voice-synthesizer guru Ray Kurzweil, Vint Cerf (father of the internet) and Mitchell Kapor (inventor of Lotus software), to say nothing of Stewart Brand, Brian Eno and Danny Hillis themselves.

Very cool, but the bets were too steep for a nonprofit wage-slave like me. Two thousand dollars was the minimum bet, and all "winnings" were to go to charity. That was more than I could give away in a single stroke.

A while later, however, I was on a list-serv in which people were talking rather broadly about the energy crisis. I tried to explain the limits of M. King Hubbert's oil data, a well as the fungibility of energy types and other such thoughts.

As usual no one was convinced of the other person's point of view, and after a point the list drifted off to other topics.

A few months later, on the same list, I mentioned that Stewart Brand had sharply reduced the money limit on a "Long Bet," and that now it was just $200 on each side. Almost immediately, Steven B. Kurtz -- one of the previous energy debaters -- asked me if I wanted to make a "Long Bet" on future energy costs.

Sure, I said. Let's make it the price of a kilowatt hour of electrical power, and let's park the bet two years into the future.

In truth, I had in mind winning the first Long Bet. I bet Steve did too.

Steve took the bet. Now, three year later, it appears he has won it, though not before a serious bit of confusion occured over at the U.S. Department of Energy which initially published data suggesting the price of electrical energy had declined.

Apparently DOE had at least two or three years worth of data wrong (including the initial price of energy at the start of our bet) due to lies, deception and data confusion that grew out of the Enron energy fiasco. In the end, looking at the re-published data, it appears the price of electrial power has gone up very slightly due to the disastrous Middle East policy of George Bush which has (among other things) resulted in a very significant decline in Iraqi oil production. Score one for Steve!

Steve and I actually have a longer, more serious bet on the human condition, in which I argue that "Over the next ten years, we will make measurable global progress in all five areas of the human condition: food, access to clean water, health, education, and the price of energy."

I let Steve pick five data sets from a closed list of about 20 options, all of which are kept by the United Nations, and which therefore have (hopefully) some continuity of collection methodology. If Steve wins on any single point, he wins the entire bet. So far, I think he is losing on all points, but the wager is still young, and we shall see.

That said, I think both Steve and I thought we really would beat Ted Danson. What was the chance that the Boston Red Sox would win the World Series in the next three years?

And yet Danson won. Though the Danson-Elliot bet seems a trifle lightweight on the surface, it's actually a wager about probability and risk, and not mere sports.

With the World Cup played only once every four years, and with far fewer Major League Baseball teams than World Cup soccer teams, Ted Danson had about a 20:1 chance of winning over Mike Elliot.

But I figured I had at least 8:1 odds of beating Ted Danson to win the first Long Bet. After all, the Sox had been losers a long time, and the window for my success was a mere two and a half years.

Of course, luck does play a hand in all things, and on this roll of the dice I lost -- twice.

Such is life.

What does all this have to do with hunting and dogs? Well, not a lot, to tell the truth. But maybe a little. I did manage to work hunting and dogs into the beginning of this piece. Now let's see if I can work it in at the end as well.

There is the small point that Thomas Malthus had quite a lot to do with the Enclosure Movement, which in turn laid the foundation for the fox and terrier work that followed, as well as the speciation of terriers following Robert Bakewell's use of enclosures to improve livestock. To read more about that see this >> illustrated history of working terriers.

Finally, for those who dig in the Eastern and Midwestern United States, the legacy of the mammoth can be found in our hedges and forests. If you are in the right thicket you may find Osage Orange, Honey Locust or Kentucky Coffeetrees.

All three of these trees have large fruits and seed pods with thick protective coatings or thorns -- natural defenses designed to help protect them from over-grazing by mammoths that roamed through this area just 10,000 years ago. The mammoths are gone, but their ghosts remain in the form of these tough and defiant trees.

Hopefully, all this will make you think, just a little, about how fragile this earth is ... about how much damage humans can do if they do not plan ... about the mammoth responsibility that comes with the powers we now have to shape the natural world.

Let's not screw it up this time .... We cannot afford to bet the farm again.

____________________________

- Note: Of the famous and smart people named in this piece, I personally know only Julian Simon and Garrett Hardin, both of whom are now dead, and Bill Paddock, who is very much alive. Steven Kurtz and I know each other only through the internet. The rest of the folks mentioned are waaaay too smart to even know I am alive. Hats off to Stewart Brand though -- he continues to nudge the world along in the right direction. Amazing. As for Danny Hillis -- he is straight off the planet. Read about him (and the mechanics of the clock) >> here

The last mammoth, a dwarf species, was killed on Wrangle Island about 3,800 years ago -- about the time the pyramids were being made.

I came across a Sierra Club page that notes: "The biggest single step that automakers could take to reduce the cost of driving is to use existing technology to make our cars, SUVs, and light trucks go farther on a gallon of gas."

I came across a Sierra Club page that notes: "The biggest single step that automakers could take to reduce the cost of driving is to use existing technology to make our cars, SUVs, and light trucks go farther on a gallon of gas."