If there was ever a stranger group

If there was ever a stranger group than young bulldog

afficionado's, I have not met them. They are a truely odd bunch of people that lurk at the periphery of the working terrier world.

On the one hand, you have the dog fighters and wanna-be dog fighters. These numbskulls range from preening fakes and short-tooled fools to sick sadists. Any way you cut it, they are a sad case with even sadder dogs.

Then you have a few romantics -- those with rich fantasy lives who imagine their cherry-eyed genetic wrecks with undershot jaws are descended from the iron-tough catch dogs of the 18th Century. They glory in leading around over-large dogs with massive heads, bowed legs, and dysplastic hips. Most of these dogs could not catch a cold, much less a pig running flat out in Texas Hill Country.

And then you have the Kennel Club enthusiasts, and their "American Staffordshire Terriers," "Bull Terriers," "Staffordshire Bull Terriers," and English Bulldogs.

Kennel Club owners of these dogs will tell you they have worked hard to breed all aggression and prey drive out of their charges. And no doubt many have. What a comical thing that is, of course -- a bit like an auto club bragging that their sport cars have no engines.

The only thing is .... it's not always true. "Bad breeding" and "poor socialization" are often blamed when dogs descended from pit and catch dogs attack small children, but ... could it be .... perhaps ... that a small bit of genetic code remains unbraided as well? It is certainly in the realm of possibility, is it not?

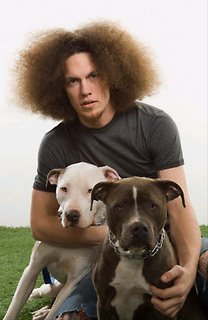

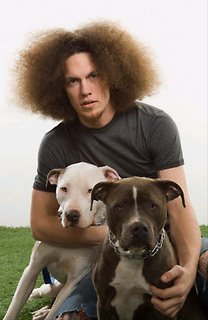

In fact, molosser breeds can make fine pets in the right hands, but many of these dogs demand much more time, energy, and commitment than their young owners realize.

A large dog in the hands of a young man with shifting interests and an unstable housing situation (i.e. most young men) is a recipie that too often leads to dead dogs at the County shelter.

There has always been a ready market for intimidating dogs, and it seems a new breed of "ancient bulldog" is created every few years. Pick up any dog magazine and there they are advertised in the back, all of them with massive bully heads: the "Alapaha Blue Blood Bulldog" and the "Olde English Bulldogge" and the "American Bulldog," sandwiched between the English, Neopolitan, and Bull Mastiffs, Rottweilers, Dogue de Bordeaux, Dogo Argentino, Fila Brasileriro and, of course, the English Bulldog. Plocked down in between are other bully-headed prey-driven defensive breeds -- Rottweilers, Akitas, Tosas, Rhodesian Ridgebacks, Thai Ridgebacks, and the like.

There have always been men with a need to display power. While the world frowns on a man cleaning an unloaded gun in a public square, it's OK for that same man to tow an enormous dog from corner to corner and park to park -- the canine equivalent of a Harley owner with straight pipes blasting through the neighborhood for the sole purpose of intimidation. If asked, the wanna-be-tough man will explain that his breed was designed to (

please pick one): kill escaping slaves, hunt jaguars, fight bears and bulls in the pits, fight other dogs, or catch semi-wild pigs and cows so they can be altered or slaughtered. You are supposed to feel

fear, and you are supposed to feel

respect for a man in control of such a powerful animal with such an ancient history.

In fact, I generally feel a little amused.The famed English Bulldog, for example, is mostly Chinese pug -- a show ring creation with legs so deformed it can barely walk, a jaw so

undershot it cannot grab a frisbee, and with a face so bracycephalic it cannot breathe. Add to these problems a deformed intestinal system (a by-product of achondroplasia or dwarfism) which makes the dog constantly fart, and a pig tail prone to infection, and you have a dog that considers its own death a blessed relief.

Other molosser breeds are not as wrecked as the English Bulldog, to be sure, but they too are largely the product of the show ring and have little or nothing to do with honest catch dogs or hunting dogs.

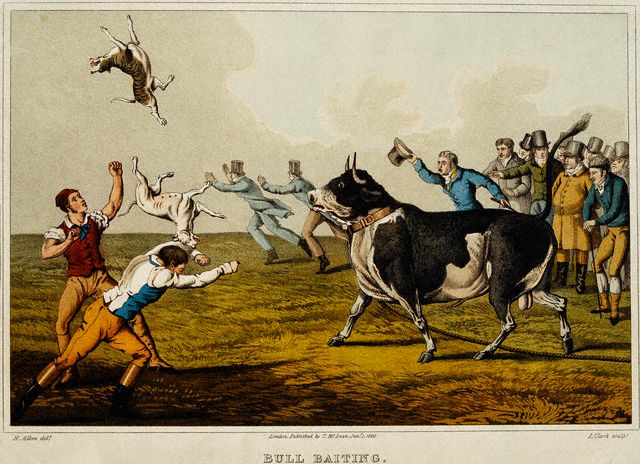

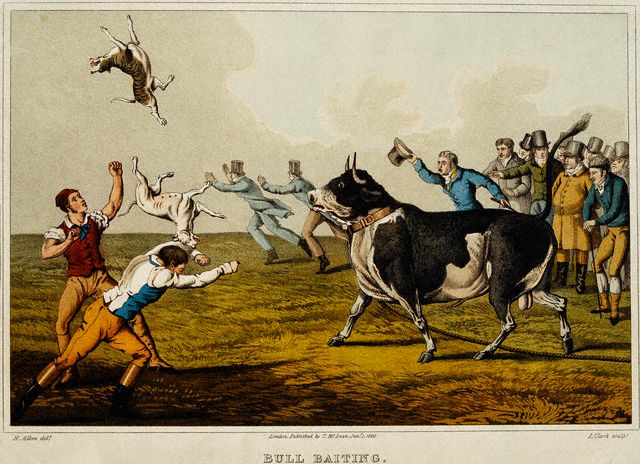

A little history is useful here. In England, catch dogs began to disappear with the rise of the Enclosure Movement of the 18th Century. As the Enclosure Movement pushed people off the land and into squalid cities and towns, boredom set in and (in the absence of television, movies, video games, and real theatre), spectacles pitting dogs against bulls, pigs, bears and even monkeys were created for entertainment, much as the

Romans had done centuries before.

The dogs used for pit work were different than the catch dogs used a century or two earlier. Pit dogs were quite variable in size, and the goal was to match the dog with its opponent (dog or beast) by weight or sense of threat. While catch dogs had to be fast to catch running stock, and tended to weigh 50-80 pounds (large enough to turn a bull or stop it, but not so large as to be slow), pit dogs weighed anywhere from 10 pounds, in the case of a small ratting terrier, to as much as 140 pounds or more in the case of bear-fighting dogs. Encounters were brief, and no nose at all was required.

Other than rat pits and cock fights, animal baiting spectacles were never common, and were banned altogether by 1835. Though secret underground dog fighting and badger baiting contests continued, they were rare, episodic, and genetically maladaptive. When police raided dog fights, the dogs were killed. When participants went to jail for other reasons, dogs disappeared. And in the era prior to antibiotics, "successful" fighting dogs often died from wounds inflicted in the ring.

In 1859, the first dog show was held. Breeds that had lost their original purpose -- catch dogs, cart dogs, pit dogs, and turnspit dogs -- soon found a new rationale for existence -- rosettes.

In the decades that followed, all manner of dogs were created, proclaimed, and endowed with invented romantic histories. That trend continues to this day.

Far from show ring fantasy and hard-dog poseurs, working catch dogs still exist. At a smaller level we have the whippet and the greyhound -- dogs designed to catch a rabbit or hare at speed. At a larger size we have the long-legged fox hounds favored by the French -- dogs that can run well and chop a fox on the fly. Added to their ranks are various sizes of cross-bred lurchers. And of course, you have the border collie -- a dog that will grip, if it has to, in order to impress upon a semi-wild hill sheep that it means business.

The penultimate cach dogs, of course, are those that work wild pig and cattle. Whether these dogs are found in Hawaii or Texas, the Everglades or Australia, the marshes of Spain, or the river banks of Central America, these dogs tend to be cross-bred dogs that, for a variety of reasons, tend to look suspiciously like rangey pit bulls.

Why is this?The answer is at least partly morphological. While a small terrier or heeler may be able to move domestic cattle or pig, and may even be able to bust them out of brush, it takes a larger and heavier dog to travel great distances and still have the weight and stamina to initimidate, and even hold, large and truely wild animals in place.

Long coated dogs, and dogs with short muzzles are simply ill-equiped to handle long runs in hot weather. Wild pigs (feral, Russian or javelina) and cattle are generally found in locations that are hot most of the year -- Florida, Georgia, Texas, Australia, Southern Spain, and Hawaii.

When a dog is running 20-40 miles a day after an animal that does not want to be caught, and which may bust in several directions at once if in a group, stopping for a drink of water or a bit of rest in the shade is not an option.

Since dogs do not sweat except through the pads on their feet, the only way a dog has of moderating its temperature is to expel heat through its mouth and sinuses. A short snout, therefore, is maladaptive for honest catch work.

A short muzzle not only makes for a dog that overheats quickly, but also for a weaker bite. In the world of predators, where consistent failure means starvation, neither the wolf nor the tiger, the hyena nor the panther, has a short face with an undershot jaw.

A short bracyophalic maxilla is also poorly designed for scent work. Whether looking for wayward cattle and pigs, or hunting jaquar or mountain lion, most catch dogs have a bit of hound crossed into them, such is the desire for nose, which almost always comes attached to a decent muzzle.

The balance point on a good catch dog changes from area to area, depending on the lay of the land, the temperature, the stock being worked, and each individual dog and owner's technique. In some areas, lighter more greyhound-like dogs may be prefered, while in others greater hound influence is the norm. Dogs may be a little smaller in thick brush, and quite a bit larger in more open country.

And yet, again and again, across the planet, the result tends to be a variation on a unifying theme -- the cross-bred pit bull.

The American Pit Bull is descended from the cross-bred stock-working dogs of the 18th and 19th Century. To the extent they have been altered, it is that modern dogs are often heavier than those found working 200 or even 100 years ago -- a direct function of the fact that most pit bulls are now found on a leash. Today the breeding of pit bulls is heavily influenced by the show ring and the picture book. As a consequence heavier, more impressive-looking animals, are favored over the smaller, faster, and more utilitarian working dogs of the past.

From the beginning, the pit bull has had a stormy career in the U.S.When it was created in 1878, the American Kennel Club refused to register pit bulls, seeing them as dogs kept by people of low breeding. The Kennel Club was interested in

dignified dogs, not

working dogs, and especially not dogs that acted as the canine equivalent of a barbed-wire and locust-post fence.

In frustration, pit bull owner Chauncey Bennet created his own registry -- the United Kennel Club -- in order to to register his own dog. Today, the UKC is the second largest all-breed registry in the U.S., and it remains a for-profit, privately-held operation.

When the "Little Rascal" movies of the 1930s popularized a pit bull by the name of "Petey," the American Kennel Club decided that the smell of cash money beat out sniffing social theories, and so they changed their

de facto position on the pit bull, while maintaining a

de jure ban on the dog.

How did they do this? Simple: they renamed the Pit Bull the "Staffordshire Terrier," and admitted it to the Kennel Club as a

terrier. In 1972, the Kennel Club changed the name of the dog again, making it the "

American Staffordshire Terrier," to distinguish it from the smaller and thicker-bodied dog of the U.K.

In fact the American Staffordshire Terrier is not a terrier in any way, shape or form. It is a Pit Bull, plain and simple.

Pit Bulls masquerading as American Stafforshire Terriers is how things more-or-less rested until the fantastic growth of dog shows and hobby breeders began in the 1960s and 70s. Suddenly a new interest in all manner of dogs was fostered, and many "old" breeds were invented almost over night.

For example, in 1970, John D. Johnson and Alan Scott registered their cross-bred pit bulls with the newly created for-profit "National Kennel Club". The name they invented: "American Bulldogs". Their goal, they said, was to get away from the "pit bull" name, which was already taking on negative connotations.

Johnson's line of dogs quickly grew thicker in the head and heavier too, as he realized that the "manly man" pet market favored intimidating dogs that could be paraded around the neighborhood or chained up in the back of a shop to scare kids away from petty pilfering. Never mind that heavy dogs with short faces could not go the distance with cattle and pigs -- these dogs were designed to sell, and what was selling was intimidation.

Alan Scott's dogs remained lighter and did not deviate too much from their working-class origins. Weighing in at around 80 pounds (often 40 pounds lighter than Johnson's) Scott's dogs also had longer muzzles and better bites. Scott and Johnson's dogs began to deviate from each other markedly, and in the end they ended up as distinct breeds with Scott breeding "Standard American Bulldogs" and Johnson a "bully" breed with huge heads that he evenually advertised as "Johnson Bulldogs".

Other bull breeds have followed suit, and other for-profit dog registries have followed on as well. Today, along with the AKC, the UKC, and the National Kennel Club, we have a host of other for-profit registries including the Continental Kennel Club, the American Canine Association, the American Hybrid Canine Club, the American Dog Breeders Association, the American Canine Registry, the American Purebred Association, American's Pet Registry Inc., the World Kennel Club, the Animal Research Foundation, the Universal Kennel Club International, the North American Purebred Dog Registry, the Dog Registry of America, the American Purebred Registry, the United All Breed Registry, the American Canine Association, the World Wide Kennel Club, the Federation of International Canines, and Animal Registry Unlimited -- to offer up only a partial list.

Among the newly minted molosser breeds are the Old English Bulldog, the Original English Bulldogge, Olde Bulldogge, the Campeiro Bulldog, Leavitt Bulldog, the Catahoula Bulldog, the Alapaha Blue Blood Bulldog, the Aussie Bulldog, the Victorian Bulldog, the Valley Bulldog, the Olde Boston Bulldogge, the Dorset Old Tyme Bulldog, the Ca de Bou, the Banter Bulldog, and the Johnson Bulldog, to say nothing of the Alana Espanol, Cane Corso, Bully Kutta, and the recreated "Alaunt."

No doubt there are many others.

Adding to the confusion, in 1972, the AKC recognized the smaller thick-bodied Staffordshire

Bull Terrier as a separate breed from the American Staffordshire Terrier, while in 1936 the Bull Terrier (still another breed) was split into two colors (white and non-white), and in 1991 into two sizes (miniature and standard).

None of these machinations have anything to do with working dogs, of course.

In the scrub country of Texas and Australia, the water hummocks of Louisiana, Spain and Florida, and the steep green volcanic mountains of Hawaii, working pig and cattle dogs look pretty much like they always have for the last 250 years. These dogs are fast, have good scissor bites, fully developed muzzles, and straight agile legs.

In the world of honest stock-working catch dogs, no one spends too much time dreaming up fanciful histories and contrived names. Whatever the dog -- pure bred or cross -- the goal is to avoid the heavy-bodied ponderous dogs so popular among the bridge-and-tunnel set, and create a dog capable to going a full day in rough country.

No one who works their terriers to ground, or uses catch dogs to chase semi-wild stock, has any confusion about what kind of dog they need to do their respective jobs, or the differences between them.

By definition, a terrier must be small enough in the chest to go to ground in a natural earth.

By definition, a catch dog has to be fast enough to catch, and large enough to hold an animal that has escape and mayhem on its mind.

Neither dog can do the job if it looks like a "keg on legs" -- an apt description of many of the molosser breeds sold in the back of pet magazines today.

The story then is an old one. In the world of true working dogs, form follows function. In the world of rosettes and puppy peddlers, form always follows fantasy. As ironic as it sounds, the blue-blazer rosette chaser and the young wanna-be bull dog man have that much in common.

.