Game wardens forced to shoot alligator

Published April 16, 2005

WEST COLUMBIA - Anita and Charlie Rogers could hear the bellowing in the night.

Her neighbors in Bar X Ranch had been telling them they had seen a giant alligator in the bayou that runs behind their house, but they dismissed the stories as exaggerations.

"I didn't believe it," Charles Rogers said. Friday they realized the stories were, if anything, understated. Texas Parks and Wildlife game wardens had to shoot the beast.

(Caption: Joe Goff, a game warden with the Texas Parks and Wildlife Department, walks past a 13-foot, 1-inch alligator that he shot and killed in the back yard of the home at the Bar X Ranch on FM 521 near West Columbia.).

Thursday, March 30, 2006

Why Nutria Are Not Hunted in Fl, TX or Louisiana

Tuesday, March 28, 2006

Frogs: Major Miracles in Small Spaces

Frogs and salamanders will soon awaken. What amazing things these amphibians are!

Think about a frog for a minute. They start off with FINS and GILLS and sucking mouths. They are, for all practical purposes, a kind of primative fish. And then the weather gets warmer, and they go through this amazing transformation in the space of about two weeks -- the sucking mouth is transformed into a JAW with a huge tongue and tiny teeth ... the fins are transformed into some of the most powerful LEGS on the planet ... and the gills are transformed into air-breathing LUNGS and an air sac that would make a bag piper proud.

It's as likely as a carp turning into a wolf. And have no doubt that a large bull frog is a wolf -- they are a top end predator in any pond.

The picture below was sent to me last summer by my friends Larry and Linda Morrison, and shows a very large common bull frog in the Morrison's yard eating a living bird! The picture at top shows the same frog digesting the meal. Wow!

A very large common bull frog swallows a bird -- alive and whole.

Thursday, March 23, 2006

Central Park Coyote - New York City

Hal the coyote is carted off for rest, recovery, vaccination and release.

A one-year old coyote was tranquilized and moved out of Central Park, New York City yesterday. This is the second Central Park coyote that I know of.

As before, the speculation is that the coyote came from Westchester, crossed down into the Bronx, and then crossed on to the island of Manhattan by way of the railroad bridge at Spuyten Duyvil — "the narrowest, safest crossing."

When the last Central Park coyote was captured in New York City, I happened to be staying at a hotel in the city. I remember the day well, as I was shaving, turned my head to see the TV and hear the story, and cut myself just before a presentation. This was in 1999. The coyote that was captured that day now resides in the Queens Zoo, and is named "Otis".

The most recent capture has been nicknamed "Hal," and he was captured shortly after taking a hungry look at a Westie being walked in the park. Hal will be vaccinated and then released back into the wilds of New York state, far from the city and traffic. God Speed.

Tuesday, March 21, 2006

Out on the Moors of Maryland

The moors of Maryland. All pictures by Chris J.

Chris J. and I went out on the Moors of Maryland yesterday -- large plowed-under corn fields with 30 mile-per-hour winds blowing cold in your lungs and heat off your body.

I had two coats in the car, but went out with a double shirt and a fleece vest and was -- for the most part -- OK as we were either moving or digging. That said, cold wind pulls the energy out of you fast!

At the first sette of the day Sailor managed to get the groundhog to crown out of the hole. The groundhog took one look at Chris, however, and decided he would try his luck underground again. That strategy worked, as he managed to dig himself in to the point that two dogs could not find him. Smart hog!

We headed down the field and checked a fox sette that was unused three weeks ago, but still open. Now it was filling in, and it was clear Mr. and Mrs. Fox had found a more likely spot to await the arrival of their kits. No worries -- too late for fox anyway.

Listening to Mountain in the hole. Sailor is staked out at left.

The dogs found again in a hedgerow next to a creek, and they were hard on the quarry when we arrived. Sailor got into the hole first, and Mountain was forced to patrol outside, checking bolt holes in the thick multifora rose brake.

Chris and I cleared out a small area, boxed for location, and began clearing soil when something bolted from a hole unseen under the multiflora. Mountain had been trying to get in at another side pipe, but at the sound of the bolt, she rushed down the creek bed in hot pursuit. She crossed the creek and began casting about for scent, and then entered a large mound of multiflora rose on the opposite creek bank.

Chris stayed with Sailor while I crossed the creek to see if Mountain had the critter bottled up. She did, and she was baying up a storm, so I called over Chris, telling him to leave Sailor -- she would come out in a minute. While Chris was crossing the creek, Sailor came out and they both crossed the creek to the opposite high bank.

Mountain had definitely found, and she was baying up a storm. The sette split off in a couple of directions, and whatever was inside was moving around pretty fast. We sunk a hole into the den pipe, and dropped a load of dirt between Mountain and the groundhog. Mountain exited, and we cleared the hole of loose dirt and put Sailor into the tight pipe. Sailor slid back up the pipe and began baying the critter again. Chris blocked off the far end of the pipe with dirt, and we began to box for location. I was barring for the den pipe when the groundhog broke though the loose backfill at the very end of the pipe. Mr. Groundhog got no more than three feet before Chris, fast as a boxer, dispatched it with a powerful shovel blow to the head.

"Hotel California -- you can check out, but you can never leave." This was an average Spring groundhog -- maybe 8 or 9 pounds and a bit skinny from losing so much weight during hibernation. We backfilled the holes, pulled the multiflora rose hedge back over the scarred dirt of the dig, and headed back to the truck.

A small Spring groundhog. The dogs like them in all sizes!

The other side of the farm was across the road. We parked past the first hedgerow and headed down the creek. The wind was fierce, and though there were holes, most of the groundhogs were still hibernating.

During this part of the year, a groundhog will clean out its hole by pushing urine-soaked dirt to the exit. This dirt, in time, will be mounded over by the action of the groundhog's body moving across it.

Along with winter den cleaning, a groundhog will also be looking to find a mate at this time of year. Once this is accomplished, a groundhog will generally retreat underground, dam itself off from wind, rain and predators, and go back to sleep for a few more weeks until the grass is greener and the temperature is a little warmer.

During the next few weeks, a groundhog may exit from the hole only once every five or six days. As a consequence, an occupied hole may appear blank to a dog. It is during this period that the semi-somnolent female will go through her pregnancy, with an average of five to seven young born in mid-April or so, just as the goldenrod blooms.

In short, the beginning of the season can be a locating challenge -- a challenge never made easier by the fact that the dirt is generally quite soft with the winter melt, making it very easy for the groundhog to dig away.

The long hedge down the creek bank had been blank. I pointed out a little copse of woods in the middle of a corn field, and suggested to Chris we give it a try. I had walked this small woods once before and remembered there were some holes.

Man were there holes! One small area looked like a Prairie Dog town. Sailor found in a very tight hole and bayed it up, but she lost this groundhog a few minutes later when it dug away.

The dogs expressed little interest in the other holes, so we headed down the slope and across a field and to another hedge.

"Hey, where are the dogs?" They had been with us a second earlier, but now they were gone. We waited in the wind for a few minutes, and I whistled, but neither one of the dogs showed up. Clearly they had found.

Chris hiked back up the slope to the copse of woods, and quickly hello'd down to me that the dogs had found just inside the forest edge. I hiked back up the hill with the tools to find both dogs deep in a sette under an intertwined mass of thick tree roots

Mountain eventually came out, blacks with soil, but entered again. In the meantime Sailor lost the groundhog in the turns of root, rock and dirt. Sizing up the thickness of the deep roots, we decided to give this sette a pass for today. When Sailor came out of the pipe, we grabbed her before she could enter another section of the sette, and we quickly walked down the hill out of the woods. Mountain came out before we had gotten too far, and I whistled her back down the hill after us.

We crossed the creek to more holes on the other side, and hunted up the hedgerow past an old cache of cow skulls. This was an old dump for diseased dairy animals and horses. There had been an old fox sette on this high field last year, but it was not there now. We crossed the creek at the bottom of the hill, but on the other side we realized Mountain had not crossed with us.

We crossed back over the creek, and sure enough Mountain had found and was hard on her game. We cleared away the multiflora rose and dug down to her.

This was a shallow dig and we found Mountain latched on to the side of the groundhog and pulling hard. Mountain was not letting go, and there was no chance to dispatch as long as the dog was latched on.

We sunk a hole behind the groundhog, hoping to be able to tail it out. We got through on the backside of the groundhog, but could not quite see what part of the animal we were looking at. At about the same time as we broke through the pipe, Mountain shifted a bit and that was enough to allow the groundhog to bolt out of the side of the pipe where we had carved it away for a photo. Damn! The groundhog raced back to ground in another small part of the sette, but Mountain was hard on her heels. After a bit more digging, Mountain located again, and we soon dropped a shallow hole and dispatched it in short order.

Two down.

Mountain gets a good cheek grip.

We crossed back over the creek again, and found an enormous push-pile of broken farm machinery and wood that had, at some point, been a large shed and its contents of rusting equipment. Mountain and Sailor were inside this push-pile in a flash, and quickly bayed up a storm.

Huge trash-strewn dump piles are a problem; it is hard to locate a dog in one, and often impossible to move material to find the quarry.

I moved around on top of the pile and located both dogs baying very strongly under a palette covered with dirt, metal, plywood and old roofing. They were not deep, and the dogs were clearly on it.

Chris and I shoved some of the roofing material and twisted metal out of the way when we both caught the stench of skunk. It was pretty strong, but not overpowering. If this was a skunk, it was not a direct hit and deep . . . but the dogs were very close to the surface and seemed to have plenty of air. What was it? Of course it had to be a vixen ... and yet, it was pretty late for such a strong scent. Was this misery or opportunity? I waffled.

Chris peered into the back of the slotted hole and said he saw red fur. Excellent -- fox. No real worries with fox. Chris said he thought he might just be able to get hold of Sailor's tail -- maybe. I told him to grab her if he could, and he did. Sailor was now tied up and Mountain was mixing it up a bit deeper than we could quite reach.

The battle was on! There was a lot of movement inside the junk pile. I wanted Mountain out if we could get to her -- no reason to risk the fox going deep into this mess of metal, boards, I-beams and roofing.

Chris peered down the slot and managed to grab Mountain by the tail and drew her out. Mountain had taken a bite in the muzzle, and it was clearly a fox. No damage done, and we decided to call it a day. If this fox had very young kits in there, she could now raise them in peace.

We called it a day -- the dogs were beat and so were we. We had accounted for two groundhogs, and dug twice that many holes. The dogs had worked a fox, and neither side of that equation were too much worse for the sport.

That night the dogs slept like rocks and I got a little sleep too. As usual, the dogs bounded out of their crates the next morning, 'raring to go.

Easy dogs. Next Sunday will come soon enough.

Monday, March 20, 2006

Exploiting Small Children for Book Sales

Am I so low that I would exploit a cute baby for craven book sales? Of course! Especially when proud papa Jason sends me a picture of his very cute baby daughter Jaelyn, who is only one day old in this shot.

Congratulations to mother, daughter and papa. And what excellent choice in reading material this little cutie has!

Jaelyn, if you grow up to be either a super model or the head of a high-powered Madison Avenue advertising shop, I hope you will remember who got you a start in the business!

Thursday, March 16, 2006

Cruft: The Man That Never Owned a Dog

Charles Cruft in 1910

Charles Cruft, pictured above, was born in 1852 into a family of jewelers. Charles had no interest in his family's business, and upon graduation from college in 1876, took a job with American James Spratt who had set up a new venture in Holborn, London selling "dog cakes".

Charles Cruft did not own a dog, but he was an ambitious dog food salesman, and traveled around England and Scotland drumming up business for Spratt. Cruft's travels brought him in contact with large estates, sporting kennels and the first commercial dog breeders in the UK.

While traveling to Europe in 1878 hawking Spratt's dog biscuits, a group of French dog breeders invited the young Cruft (just two years out of college!) to organize and promote the canine section of the Paris Exhibition, which he did.

Upon returning to England in 1886, Crufts took up the management of the Allied Terrier Club Show at the Royal Aquarium at Westminster, with an eye towards making money.

The first formal "Cruft's Show" was booked into the Royal Agricultural Hall, Islington in 1891. This was the first in a long series of dog shows that Crufts held there, each of them making an appealing profit for Cruft who still did not own a dog himself.

In 1938 Charles Cruft died (still having never owned a dog!) and his widow ran the 1939 Crufts Dog Show. Three years later Mrs Cruft felt the responsibility for running the show too demanding and, in order to perpetuate the name of the show her husband had made world famous, she asked the Kennel Club to take it over and it was sold to them. The 1948 Crufts Dog Show was the first under the Kennel Club auspices.

This year, the Best in Show winner at Crufts was an Australian Shepherd from the U.S. A wire fox terrier placed second.

Tuesday, March 14, 2006

Another Dig, Same Day

Chris checks out the hole action on the last sette of the day, while Mountain guards the exit.

Chris and I loaded into the truck and headed up the road and around the corner to another farm. We met the farm manager's wife at the entrance and she noted I had a new vehicle. Yes ma'am. Got me a new used Ford Explorer! The farm manager was under a tractor doing some work, but he came out from under and we chatted for a few minutes. Very nice people.

Chris and I started off at an old feed bunker where I have bolted a few raccoon. The hole in the side of the bunker is impossibly small, but Sailor got in (just barely) and she bayed it up and then went deeper. Too bad. The trick with this feed bunker is to hope Sailor (the only dog I know small enough to get into this particular location) can catch the coon or the groundhog resting in the upper hollow part of the bunker, rather in the dirt sette underneath it, as the bunker cannot be destroyed. Sailor came out (I suspected, from the rather uninvolved way she was acting, that it had only been a rat) and I scooped her up and put her into the truck for a short ride into the middle of the farm.

Mountain had been struck in the truck all morning due to her recent surgery, but had been begun barking like a madman when she saw Sailor enter the feed bunker. Now I decided to let her out with a locator collar on so she could do a little locating.

We headed over to a dry flint ridge which proved blank, but Chris got to see how much stone these groundhogs can move out of a den pipe -- and how small and tight those pipes are in hard ground. Why so small? Simple -- groundhogs don't have dynamite.

We walked past a few blank field holes to a lightning-shattered tree at the far end of the farm. This old sette is actually three den pipes right next to each other. As luck would have it, the dogs found in the deep part of the sette which dives almost staight down under massive roots. The ground here is shot through with seams of slate, and I have picked a dog up at 10 and 12 feet. Without at least three diggers, and maybe a chainsaw, this hole was not worth starting. Quarry is too plentiful to spend so much time and risk at a single dig.

Chris and I pulled back a bit to encourage Sailor to come out (she generally will if she hears no digging or movement top side). Bingo, Sailor was out, and after a few minutes, Mountain was too. Mountain looked a bit alarming, as she had taken a small bite over one eye and the blood had made a startling red ring around here eye. A quick examination showed it to be only a slight boxing cut above the eyebrow. No worries.

We headed across the farm and found a few more holes, but they were all blank. The sky was getting a little threatening, and I suggested we try a sette in the large open Morrison shed where the combines and some of the large round bales were stored.

Sure enough, after a few minutes of mucking about, the dogs located something and Sailor opened up to a nice solid bay.

Chris and I shifted a large round bale and slid a pallet aside and tired to locate, but the dogs were moving all over the place underground. Mountain could block a hole and enter part of the sette, but most of it seemed too tight for her.

We let Sailor push it around a bit but it never quite settled. We eventually decided on a location and began to dig -- if nothing else we could cut the sette in half.

The soil was dry and compacted here -- a product of massive bales and machinery pressing down on dry ground for many years. We eventually cut into the pipe about three feet down, and Sailor bayed it up and we could hear a little bit of snarling below. Chris pointed to some raccoon scat near the hole, and I thought there was possibility that might be what we had in the hole. Hope so!

We cut one more hole into the sette right on top of the groundhog which quickly decided that now was a good time to bolt. Mountain, who had been unable to get into the pipe much more than her shoulders, backed up a bit and grabbed the groundhog as it bolted, and then Sailor was on it too. For a brief moment there was a little excitement as the two dogs rolled the groundhog. I quicky got a boot on the groundhog to prevent it from biting the dogs. That done, it was quickly dispatched. This female weighed 10 pounds and had a 13" chest.

This was a good day in the field as quarry was accounted for, the dogs were uninjured, and my body did not feel too beat up from the experience of lugging tools solo across the farms.

Chris was great company and a ready digger who is approaching the world of digging dogs sensibly; seeing what actually works in the field and what is really needed in a dog.

Theory ends at the hole, and ultimately you have to find a dog that will work for you and the way you work (barn or dirt), the quarry you dig, and the ground you dig on.

If you dig only a few times a year, a hard dog that is laid up with injuries is no constraint on your next dig.

If you mostly show dogs and only dig a few times a year, you may be able to get by with a larger dog -- there are always a few pipes that even a large dog can get in to.

That said, if you dig week in and week out, you are looking for smaller, not larger, and too hard a dog becomes an expensive tool and an economic and emotional liability.

A little rag after a quick dispatch.

Nice Weather, Good Soil and Good Company

I went out Sunday with Chris J. who is new to terrier work but very sensibly studying up before committing to a dog that might otherwise be a 15-year mistake. We met at the infamous "Flint Hill Country Store" and then headed off to some public land for a scout. Mountain was with me, but I left her in the truck as her stitches from her hernia operation had just come out the day before, and she has yet to "hair over".

I could tell Chris was a bit skeptical of Sailor -- she's a little dog, and in truth she does not look like much. No matter. She always proves herself soon enough. Not all that is gold glitters, and in working dogs it often does not.

The land we head out on to is an old farm that the state bought up to use as a Wildlife Management Area (WMA). Some of the land is leased back to the farmers -- cover crops like corn and alfalfa have a symbiotic relationship to the deer and turkey that are hunted on the WMA. The farm is slowly being "re-wooded" by the silly people at "Global Releaf". More on that later. Suffice it to say that we found den pipes among the tree plantings at the edge of the fields, as I knew we would.

I had scounted this area for fox settes in January and even under the snow I could tell there were enough holes to make me happy. This old farm was thick with fox tracks, but though I looked with two good locating dogs, I never did find an occupied fox sette. In my defense, this was the warmest winter I can remember, and there were not more than two good cold foxing days on which to look.

The first week of March is a bit early in the groundhog season. As a consequence, the first six or seven holes were blanks, but we headed off to a bit of land next to a point of woods where I suspected we would find an occupied hole, and sure enough we did.

Sailor poked around a bit at the mouth of a promising sette, and then slid in and opened up. She had definitely found, but the ground was pretty soft and, after a few minutes, she lost it and then found it again.

This went on for a few minutes, and I let her work it out. Groundhogs in really soft ground can almost swim through the soil. This was not the real soft stuff you get after prolonged rains, but it was soft enough for the groundhog to wall itself off from the dog in short order, and it did so at every opportunity.

Chris got a pretty good idea of how tight these pipes are -- what looked like a very large hole at the top quickly narrowed down and took a hard turn at the bottom of a two-foot drop. A small dog clearly has its uses.

After a bit of poking around, Sailor seemed to have located, and we sunk a hole down to her, a little over four feet deep. By the time we got down to her, she was a little ahead of where we started, and we decided to come in behind the critter with a second hole, which we sunk in short order. After digging the second hole and cleaning it out, we let Sailor bay it up for a bit. This is the part of terrier work I like -- the dog's genetic code exploded, tail wagging, the quarry in the pipe, the digging mostly done, the dog clearly safe from skunk.

After a bit of listening to Sailor bay it up, we pulled her from the first hole and dropped her in the second hole, where she came up fast on the groundhog's butt. In short order the groundhog tried to bolt, and it was dispatched to Hog Heaven.

This was a nice dig on a very pleasant day, with excellent soil on land that I think will be quite productive. We weighed this groundhog who was three nickels shy of 13 pounds -- a nice weight considering this animal had probably lost at least 3 pounds in hibernation.

We had finished up the dig by 10:30 or so, and we scouted around a bit more before heading back to the truck, to try our luck on a nearby farm where I thought we might be able to raise a raccoon. Variety is the spice of life and always good.

That second dig will be a story for another day, as duties other than typing now call . . .

Ted Williams on "Global Releaf" Projects

__________________________________

Trees Can Be Just Another Sacred Cow

by Ted Williams from High Country News

__________________________________

Only God can make a tree, but anyone can ruin a prairie. Consider the celebrated 19th century journalist Julius Sterling Morton. On moving to Nebraska from Michigan in 1854, he found he didn’t like the way nature had designed the Great Plains. Accordingly, he summoned forth "a great army of husbandmen… to battle against the timberless prairies."

In 1885, Morton’s birthday became a state holiday we all just noted called "Arbor Day." A statue of him, paid for in part by the pennies, nickels and dimes of school children from all over the world, now stands in Nebraska City. Arbor Day is celebrated throughout our land, and when you join the National Arbor Day Foundation you get 10 free tree seedlings that may or may not belong in your area.

There are or were prairies in most of our nation, not just the plains states. Prairies used to dominate the San Francisco Bay region, but as Arbor Day euphoria swept west, locals planted trees — including eucalyptus, America’s biggest weed — thereby wiping out native ecosystems. By 1949, the trees had killed off the remnant population of the prairie-dependent Xerces blue butterfly, making the Presidio of San Francisco — an old Spanish garrison — the site of the first documented butterfly extinction in North America.

In 2002, American Forests, the nation’s oldest conservation organization, and its "Global ReLeaf" partners, which included such spewers of tree-killing and greenhouse gases as Conoco, Arco Foundation, Baltimore Gas and Electric, Edison Electric Institute, Metropolitan Edison, Texaco, Octane Boost Corp., and Pennsylvania Electric, reached their goal of planting 20 million trees across the United States. There was little thought about what species belonged where and no recognition that lots of places had too many trees already.

Sandra Ross, director of the conservation group Health & Habitat of Mill Valley, Calif., wanted to sign up for Global ReLeaf but couldn’t extract a promise from organizers to plant only indigenous trees, and only in areas that used to have trees.

"I have trouble talking to these people who have this wonderful enthusiasm for planting trees," she told me. "Most of them don’t have any idea of site-endemic situations. ‘We’re gonna plant trees!’ they’ll say, and I’ll ask what kind. And they’ll say, ‘I don’t know; they’re in little pots.’ Mill Valley (in the Bay area) doesn’t need a tree-planting program. It needs a tree-removal program."

Just such a program is under way at the 3,334-acre Union Slough National Wildlife Refuge near Titonka, Iowa, where the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service is trying to restore a tiny piece of tallgrass prairie, a globally endangered ecosystem supporting 300 plant species per acre and critically important to vanishing grassland birds.

But when managers suggested cutting and burning invasive trees, the public accused them of "playing God" and initiating "a scorched earth policy." School kids blitzed them with e-mails, begging them to desist from arboricide. With the kind of courage that doesn’t get recognized enough in federal service, the staff forged ahead, cutting, burning and educating where it could. Although the locals have more or less quieted down, the refuge finds itself strapped for money and manpower.

"I’m frustrated," declares federal biologist Tom Skilling, who reckons that only 10 or 15 percent of the trees have been removed from the project area.

There’s a notion, old as the Oregon Trail, that trees prevent erosion in prairie habitat. "Not true," says Rich Patterson, director of the Indian Creek Nature Center in Cedar Rapids, Iowa. "As a general statement, dense growths of trees reduce the ground cover of sedges, grasses and forbs, and there’s a lot of sheet erosion in the woods. These ground-huggers do a better job holding soil than trees."

For his radical notions, Patterson used to get pilloried by tree lovers, including state and federal bureaucrats who had devoted their careers to planting trees for "conservation." Now, after 29 years of cutting, burning and educating, he’s got everyone pretty much behind him.

Still, the old mindset dies hard. Even today, the Farm Bill’s Conservation Reserve Program impedes prairie restoration. It requires landowners wanting to enroll marginal riparian pastures to plant trees and shrubs.

Depending on where and how it takes root, a tree can be lovelier than a poem or uglier than a road-killed coyote. I’ll withhold comment on Joyce Kilmer’s verse except to say I prefer the words of Ansel Adams, worth perhaps more than one of his photographs, and with which he helped quash a Boy Scout tree-planting project on California’s Marin headlands: "I cannot think of a more tasteless undertaking than to plant trees in a naturally treeless area," said Adams, "and to impose an interpretation of natural beauty on a great landscape that is charged with beauty and wonder, and the excellence of eternity."

______________

Ted Williams is a contributor to Writers on the Range, a service of High Country News (hcn.org) in Paonia, Colorado. When not roaming the West as an outdoors writer, he lives in Grafton, Massachusetts.

Monday, March 13, 2006

"I'm with the Band"

You are invited to A Picnic Concert at

in aid of the

Saturday 20th May 2006

THE BAND DU LAC

Featuring: Gary Brooker – Mike Rutherford

Andy Fairweather Low – Paul Carrack

with special guests

ERIC CLAPTON l ROGER TAYLOR

NICK MASON l ROGER WATERS l

GEORGIE FAME l ROGER DALTREY

and supporting bands

Tickets £75

Numbers strictly limited Ticket Hotline: 0871 919 8321

To book online: http://www.countryside-alliance.org/highclere/

Gates open from 4pm Bring or order a picnic Champagne, wine & Pimms bars BBQ, deli, crepes & coffees

Sunday, March 12, 2006

The Working Bedlington

This book, by John Glover, is said to cover all aspects of choosing, keeping, breeding and working Bedlington Terriers, and includes important information on the history of the breed and how the working type has been kept alive. There is also a chapter on the increasingly popular Bedlington Lurcher. The author is said to be a well known figure in the Bedlington terrier world, "and has played a major part in the resurgence of popularity this type of Bedlington is now enjoying."

In fact, I do not think it is too much of a resurgence -- though there is no doubt people are trying. Bedlingtons are still uncommon in the field as they are quite large and prone to some very serious health problems. In addition, among most of the Bedlingtons I have seen, the coat is very linty and does little to keep the animal warm and dry in bad weather. A Bedlington x Greyhound or Whippet is a popular small lurcher, however.

>> To order a copy of this book, try Coch-y-Bonddu Books ( http://www.anglebooks.com ) or Read Country Books ( http://www.readcountrybooks.com ) I can vounch for both sellers -- great service and fair prices for hard-to-get books.

Wednesday, March 8, 2006

The Legal Construct of Hunting with Terriers

As a type of hunting, terrier work is inefficient, very selective, and almost never results in an animal being left to die wounded and unfound. In addition, terrier work generally allows an animal to be moved off a farm if that is required or prefered, and all of the animals hunted with terriers in American are at historically high population densities.

As a type of hunting, terrier work is inefficient, very selective, and almost never results in an animal being left to die wounded and unfound. In addition, terrier work generally allows an animal to be moved off a farm if that is required or prefered, and all of the animals hunted with terriers in American are at historically high population densities.In this sense, terrier work is an ideal form of nuisance animal control, and one of the very best forms of hunting.

Inefficiency means that terrier work cannot have a major impact on animal populations over a wide area, but can knock down a selected type of nuisance wildlife on a farm.

Selectivity means that, unlike trapping, there is little or no bycatch, and animals can easily be allowed to bolt off unharmed if that is desired.

Humaness and safety are raised to an art because if animals are terminated (and they are often let go) it is done swiftly in the den with the efficiency of a direct bolt to the braincase -- there is very little chance that a young animal will be left orphaned, that a shot will not be terminal, or that a bullet will whiz to places unintended.

Since American terrier work is focused solely on animals at a historically high population abundance (groundhog, raccoon, possum, and red fox), thinning out these populations is more likely to be helping a farm environment return to balance, rather than move it out of balance.

Finally, there is the fact that terrier work, like all hunting with dogs, is a real economic engine. Hunters spent more than $605 million on their hunting dogs last year -- well more than the $513 million skiers spent on ski equipment. If the average working terrier enthusiast sat down and calculated how much he or she spent on their dogs every year (travel, gasoline, hunting licenses, veterinary care, fencing, purchase of special vehicles, etc.) they might find the financial outlay rather shocking. A $200 groundhog? A job created for every person that actually digs in this country? Easily.

In the U.S., working a terrier or lurcher is a rare enough occurence that the practice is not covered by one law, but by a confusing tapesty of laws that change from state to state, location to location, season to season, and from quarry animal to quarry animal. That said, terrier work is clearly legal provided that some basic rules are followed.

Before we get into those rules, however, a review of the basic rationale behind our hunting laws is perhaps in order. The reason we have hunting laws at all are : 1) safety; 2) maintenance of stable and sustainable animal population numbers, and; 3) revenue collection to fund land and wildlife conservation programs (including the protection of nongame species).

Now for a general overview of the law and the rules of thumb. This is a broad overview; please consult state and local wildlife laws for specific regulations governing hunting in your area.

Hunting License: No matter what you are hunting, whether on public land or private, you should have a valid state hunting license. Having a current hunting license on your person while hunting will solve a lot of headaches should you run into a game warden or accidently trespass on a neighboring farm. If you are on a one-day excursion out of state, and solely hunting groundhog, I would suggest confining your terrier work to private farms with all dispatch done by a state hunting license holder.

Guns: Discharge of a gun is generally illegal within the line of sight of a building or near a road, even if you are shooting down a hole, and as a consequence the legality of using a gun for dispatch may change not only from farm to farm, but from location to location on a farm. Guns are not necessary for terrier work, and I suggest not carrying them at all. If you do not have a gun, and are simply working a dog, many states do not consider you to be hunting at all. The presence of a gun instantly changes the liability equation for a farmer (or his neighbor) and the legal threshold for any violation that might accidentally occur (such as trespass). If dispatch is needed (it often is not), it can be done swifly and efficiently with a blow to the head with the back of a machete, digging bar or (in a pinch) a shovel. If you have a hunting license with you, and you do not have a gun, you have avoided the two biggest legal headaches you may encouter while hunting in the field.

Private Lands vs. Public Lands: As a general rule, terrier work on private land with permission from the land owner is less regulated than terrier work on public land. In most states (but not all), nuisance wildlife may be legally dispatched on private land year-round, and there is little or no chance of encountering a wildlife control officer if you stay away from major roads. When hunting in public Wildllife Management Areas, always have a hunting license with you and be aware of the season. If it is deer hunting or turkey season, you must wear a hunter-orange hat and/or vest, and some serious thought should be given to whether you want to have loose dogs on the ground at all. Most deer hunters are shooting from fixed blinds, however, and if you know where those blinds are, and stay away from them, you should be fine. When working public lands, be aware that cutting trees and brush may be illegal and as a consequence as little cutting back should be done as possible. A parachute cord in your kit can often be used to pull brush back, obviating major cutting around a digging site.

Fox and Raccoon: In most states, fox and raccoon have late-fall and winter hunting seasons, and hunting these animals is regulated by the season for furbearers. The term furbearer is a term of art that refers to a specific list of animals in each state, not the actual presence of fur. In most states, groundhogs are not considered furbearers, and skunk and possums may be exempt as well. Some states (such as Virginia and Maryland) have widely divergent laws for fox hunting that may change from county to county. In some Maryland counties, for example, fox may be hunted and killed year-round, while in others they can be chased year-round but not killed (note that both laws were written by mounted fox hunters for mounted fox hunters). In general, fox hunting in Maryland (as in most states) is legal in season, while fox hunting without a gun and with dogs alone is legal all year long. In many states it is illegal to destroy the den of a fur bearer (a term which does not include a groundhog). In reality, this law does not make much sense, as fox dens are routinely destroyed when farmers plow their corn fields in May. That said, the intent of the law seems to be to protect fox dens with young inside, and a wide birth should be given to possible fox dens between March 1 and the end of May when that condition is most likely to hold true. If at all possible, it is best to bolt fox from dens rather than dig them, and this is especially true on public lands.Groundhog and Possum: Groundhog are considered an agricultural pest in most states where they are prevalent, and most state games law reflect that position. For example, in Maryland and Virginia, there is a ban on Sunday hunting, except for groundhogs on private property and unarmed fox hunting with dogs (i.e. terrier work as I practice it). In addition, in most states there is no season on groundhog hunting, nor is there a bag limit. In Virginia, the only other other animals with similar "open season, unlimited take" provisions are rats and pigeons, which should give you some idea of where groundhog fall on the protection pecking order. Possum mortality is naturally high (about 90 percent a year), and in many states these animals are not classified as protected wildlife.

Relocating Animals: In order to reduce any chance that someone might accidentally trap and move a rabid animal to a new location, most states make it illegal to move wildlife. If you are relocating a nuisance animal, do not move it very far -- a few miles is generally enough to get if off the farm, with little chance it will return.

Discretion, Common Sense and Stewardship: Terrier work, like all hunting, should never be done near roads, foot paths or parking lots. If you are working legal public lands (i.e. a Wildlife Management Area), priority should be given to others in the area, whether they are birders, hikers or deer hunters. Your goal should be to keep a low profile, avoid drawing attention to yourself, and to leave the land as you found it. Close all gates, do not drive on to soft ground or planted fields, and do not trespass. All holes should be well filled after being dug, and the raw earth covered with such forest and field detritus as can be found. If you are taking new people out, take the time to teach and lead by positive example. There are fools engaged in all types of activity, including hunting. Try not to be one of them.

Are you going to be OK, in terms of the law, if you follow the basic points laid out above?

I think so, but you need to spend time researching state and local game laws at your Department of Natural Resources' web site. The typical DNR does not make this easy, especially if you are not doing something as traditional as deer or turkey hunting. That said, if you root around on the typical DNR web site, you should find some variation of the core points set out above.

Happy hunting!

Friday, March 3, 2006

Wednesday, March 1, 2006

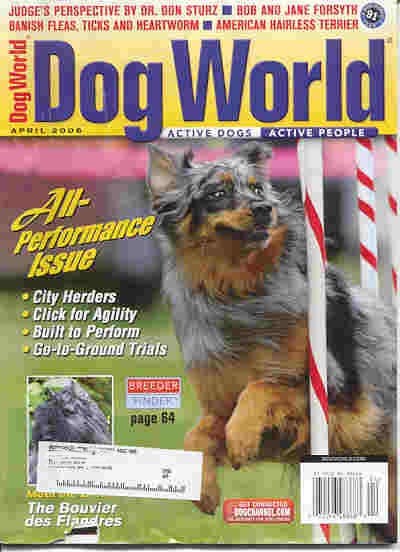

Go to Ground in Dog World Magazine

For those interested in go-to-ground trials (JRTCA, American Working Terrier Association or AKC), I have a pretty basic introductory article in the April issue of Dog World magazine, available at Borders and your better book stores and magazine racks, and >> by subscription.

A longer section, on the same subject, can be found in American Working Terriers. Nice to see that the article got a bullet point on the cover!

And no, I do not do much go to ground! If I have a weekend to spare, it's not at a show or a trial of any kind, but with family at home or honest hunting dogs in the field.